A team of researchers from the Wallenberg Wood Science Center has created the world’s first wooden transistor, a device that could have potential applications in biodegradable computing and implanting into living plant material.

The transistor is made of balsa wood, a species chosen for its structural stability, strength and ability to efficiently transport water and nutrients. Pieces of balsa wood were treated with heat and chemicals to remove much of the lignin, making more room for conducting materials. The remaining cellulose-based structure was then coated with a conducting polymer known as PEDOT:PSS, which was found to be the most effective in part because it is water soluble. The polymer decorated the insides of the wood’s pores, allowing the wood to conduct electricity along its fibers.

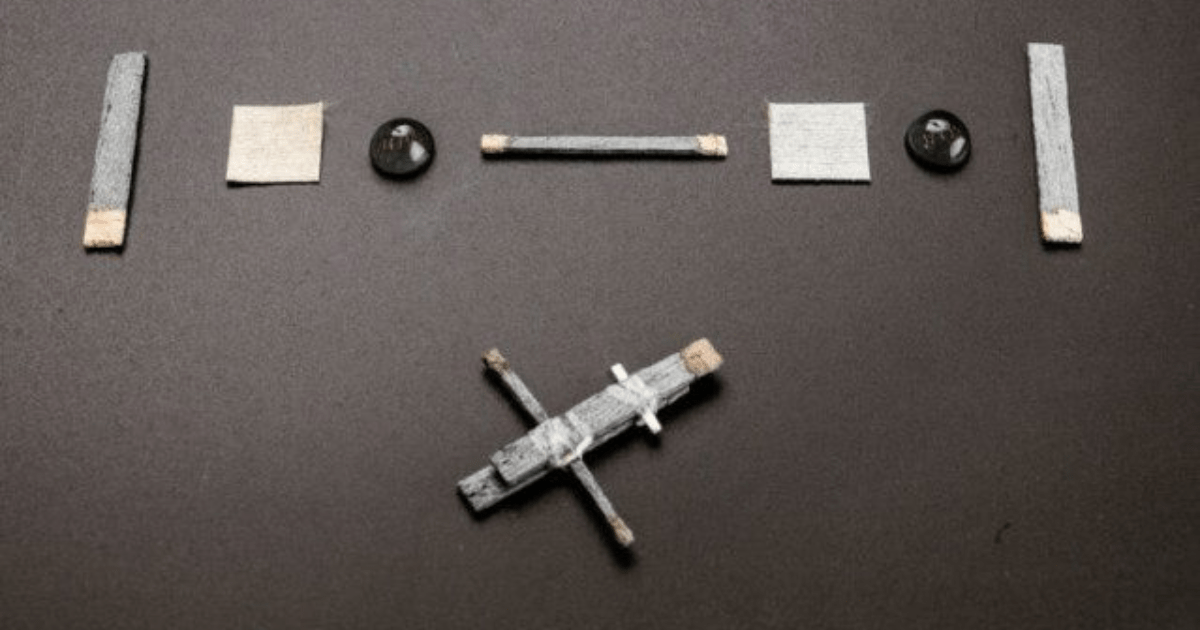

To assemble the transistor, the researchers used three pieces of conducting wood arranged in a T shape, with the top of the T serving as the transistor channel, and a source and drain at either end. The channel was sandwiched between two “gate” pieces, forming the leg of the T.

At the points of contact between the channel and the gates, the researchers layered a gel electrolyte. A voltage applied to the gates delivers hydrogen ions from the electrolyte into the polymer, causing a chemical reaction that changes the conductivity of the polymer. This reaction is reversible, allowing for the on-off operation of the wood-based transistor.

While the wooden transistor is not expected to serve as the basis for complex electronics, it may find uses as an on/off switch for other components, such as solar cells, batteries or sensors that may be incorporated into wood, dead or living. The researchers say higher currents and smaller devices should be possible to engineer, and the transistor’s self-supporting property could be an advantage in creating sustainable devices. The team is also exploring the possibility of integrating electronic functionality into living plants.

“This is really just the beginning,” says Daniel Simon, a professor of bioelectronics at Linköping University who was not involved in the work. The wooden transistor, which is 3 centimeters across and switches at less than one hertz, was created in the spirit of collaborative curiosity.

“It was very curiosity-driven,” says Isak Engquist, a professor at Linköping University who led the effort. “We thought, ‘Can we do it? Let’s do it, let’s put it out there to the scientific community and hope that someone else has something where they see these could actually be of use in reality.’”

![[CITYPNG.COM]White Google Play PlayStore Logo – 1500×1500](https://startupnews.fyi/wp-content/uploads/2025/08/CITYPNG.COMWhite-Google-Play-PlayStore-Logo-1500x1500-1-630x630.png)